Chemistry's green future takes root in Flint

You've heard of PFAS. It stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; thousands of chemicals that have been commonly used in products like Teflon cookware, food packaging, and stain repellents. Several PFAS chemicals can be detrimental to human health; studies have found effects ranging from increased cholesterol levels to pregnancy complications and a higher risk of cancer.

PFAS are also called "forever chemicals," a name earned by the fact that they persist for incredibly long periods in the environment. A 2018 study from the State of Michigan showed that more than 1.5 million Michigan residents have consumed water containing some level of PFAS.

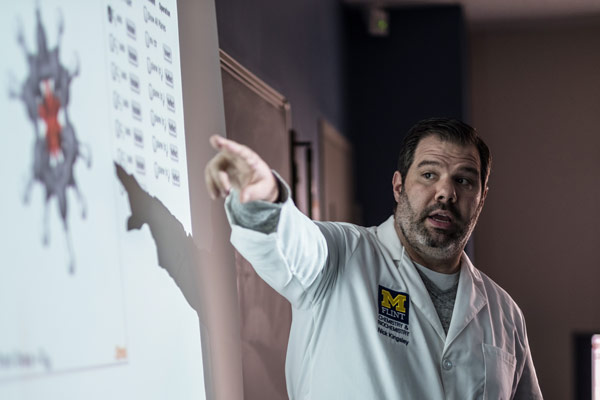

"PFAS have been very effective in their intended uses, but have negative environmental and human health effects that are causing problems around Michigan," says Nicholas Kingsley, associate professor of inorganic chemistry at UM-Flint. He goes on to explain that it is vital for chemists to think about the negative effects of chemicals before they are designed and implemented. "If we understand that certain features of a chemical will likely make a substance toxic to humans or the environment or are going to persist for long periods of time, then we should avoid those features when designing chemicals."

While government agencies are working to remediate PFAS in the environment and regulate its use, Kingsley and other professors in the UM-Flint Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry are training the next generation of chemists to avoid making similar mistakes through an innovative subfield called Green Chemistry.

"The focus of Green Chemistry is not just to create more sustainable chemical products and processes—they also have to be cost-effective and they have to work," says Amy Cannon, who holds the world's first PhD in Green Chemistry and is the executive director of Beyond Benign, a nonprofit devoted to Green Chemistry education. "It's a common platform and language that adds value for both the sustainability folks and industry." In 2013, UM-Flint signed Beyond Benign's Green Chemistry Commitment—pledging to continually improve the implementation of Green Chemistry learning objectives for its students.

Not content with only being a commitment signer, UM-Flint introduced the first Bachelor of Science in Green Chemistry in the fall of 2018. As the only undergraduate degree of its kind in the United States, the program provides the same preparation that traditional chemistry programs offer with additional areas of emphasis in fields such as life-cycle engineering, toxicology, and public policy.

"We can do everything we can as chemists to create safer products and processes. But if the policy doesn't keep up, we still have an uphill battle," explains Kingsley. "The Flint Water Crisis wasn't just a chemistry problem … It was also bad policies and decision-making that caused it to happen."

Nicholas Wills, a senior majoring in Green Chemistry, gave his input on the creation of the program as part of a committee composed of industry leaders, professors, alumni, and students.

"What drew me to the Green Chemistry program was the challenge of it. You have to think not just environmentally, but fiscally and efficiently as well," Wills says. "It allows you to place your chemistry learning in context."

Context is important for Wills, who plans to attend graduate school before working in research & development for the pharmaceutical industry. While taking CHM 372: Green Chemistry, he learned about the requirements companies like Merck Pharmaceuticals set for reducing waste in chemical reactions.

"Industry is really asking for students with these skills," says Cannon, who worked for companies like Gillette before co-founding Beyond Benign. "We're seeing more job descriptions that are calling out Green Chemistry because companies see the value of students with the skills to actually solve these complex problems."

At UM-Flint, thinking in Green Chemistry terms isn't limited to the major; the entire Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry has embraced its guiding principles. Professors challenge themselves and students to think about their laboratory practices; Wills remembers how he worked with professors to change a process used to produce a compound commonly used in lab classes—they reduced the number of steps needed, and therefore, the amount of waste produced.

The Chemistry Club, a student-run organization, recently received a Green Chemistry Chapter Award from the American Chemical Society's Green Chemistry Institute for educating their campus and community about Green Chemistry. Among their activities, the Chemistry Club held demonstrations in over fifty local K-12 science classrooms, many of which included Green Chemistry.

These activities and more speak to the missions of the College of Arts & Sciences and UM-Flint as a whole – students and faculty working with the community to advance each other both locally and globally.

Cannon says, "Green Chemistry education doesn't just produce chemists, you get problem solvers and collaborators; people who know how to ask the right questions. You're getting a different kind of thinker, and that's very valuable."

Related Posts

No related photos.

- Chemistry & Biochemistry

- College of Arts, Sciences & Education

- Community

- Faculty

- Learning By Doing

- Research

Logan McGrady

Logan McGrady is the marketing & digital communication manager for the Office of Marketing and Communication.