Literacy education grads help Michigan school districts and families improve reading

The numbers are scary.

- Michigan ranks 35th in the country for fourth-grade reading skills.*

- Among 11 states with test data from 2014 to 2016, Michigan saw the biggest decline in third-grade English language arts proficiency: 50 percent to 44.1 percent.**

- In Flint, third-grade reading proficiency plummeted from 41.8 percent in 2013 to 10.7 percent in 2017 — a nearly 75 percent drop overlapping the height of the water crisis.***

Part of the decline can be explained by higher standards and a new online exam format put in place in 2015. But the trend is clear and confirmed by a recent Brookings Institution analysis: among all US states, Michigan students have made the least improvement on National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) scores since 2003.

In response, Michigan's legislature passed a law in 2016 requiring students more than a grade level behind in reading skills be retained in the third grade. That law takes full effect starting this school year. However, results of a spring 2019 poll by Education Trust-Midwest found 67 percent of Michigan parents knew little or nothing about the law.

Diane Richards, principal at McMonagle Elementary in Flint's Westwood Heights school district, understands how difficult it can be to get parents engaged in literacy initiatives.

"We're dealing with the water issue; we're dealing with families who are struggling," said Richards, "so literacy and reading with their children sort of falls to the bottom of the list."

As a graduate of the University of Michigan-Flint's master's program in literacy education, Richards learned to put the whole family at the center of strategies to improve reading.

According to UM-Flint Education Department chair, Mary Jo Finney, PhD, this emphasis on the family was woven into the fabric of the literacy education program and its reading center at their launch in the late 1990s.

"At that time lots of universities had reading clinics, but the focus was primarily on the education of the graduate or doctoral students," Finney explained. "Our reading center is about really helping the children and families in the community. And that's another way of educating our students. They're not just doing the work of a clinician — diagnosing and addressing individual reading problems — but learning how to do work that actually helps an entire community."

Suzanne Knezek, PhD and coordinator of UM-Flint's literacy education program, noted that while Flint faces special challenges, every community has its own mix of issues that impact literacy.

"I see Flint as a tremendously unique place," Knezek said. "But it's also the kind of place that shares the same kinds of difficulties you find anywhere in this country. So we need to think about what's really happening in all communities — urban, suburban, and rural."

Richards has implemented many lessons learned in UM-Flint's literacy education program at McMonagle Elementary — especially those to boost family participation. Kindergarten graduation ceremonies are moments to build pride in educational achievement and deliver messages about the importance of reading together. She has opened up the school's library during the summer for families to check out books. And this year's summer school programming was revamped to focus solely on the literacy needs of kindergarten through second-grade students.

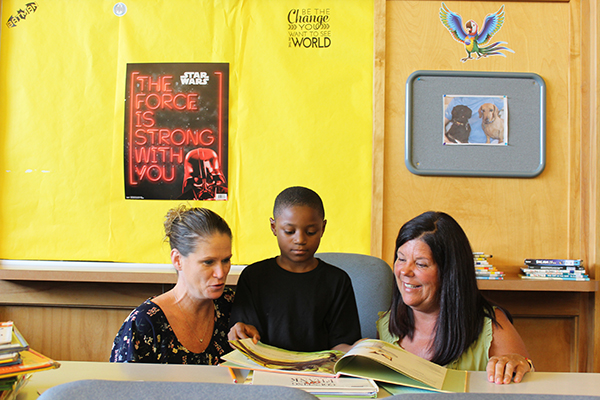

Last year, thanks to a grant through the Genesee Intermediate School District, Richards was able to hire her school's first literacy coach, Kristie Yammine — another graduate of UM-Flint's literacy education program. In that role, Yammine works with teachers to improve literacy instruction. She gives presentations during professional development workshops, models lessons for teachers, and helps them secure resources.

Having worked in the district as an elementary teacher for thirteen years prior to taking on the role of literacy coach, Yammine sees how their efforts have changed the culture of literacy for students, families, and teachers.

"It will take more than one year to really gain the trust of everyone and get everything moving in the right direction, but we're working as a team and I'm hopeful that we'll see more improvement in all facets," said Yammine.

When asked about the most important thing for parents to understand about Michigan's third-grade reading law, assistant professor Chad Waldron, PhD, said it is important for parents not to panic. He said the new law does not change the fact that literacy is complex, that every child learns in a different way and at a different pace, and that parents must continue to advocate for the educational experiences and outcomes they want for their children.

Waldron added that UM-Flint's decades-long commitment to early childhood and literacy education will continue to serve students, families, educators, and entire communities.

"That work is always going on, always important, and we are committed to doing the day-to-day work that will continue to help all children be successful."

* Detroit News analysis of 2017 National Assessment of Education Progress data

** Education Trust-Midwest

*** Detroit Free Press analysis of 2017 National Assessment of Education Progress data

Related Posts

No related photos.

UM-Flint News

The Office of Marketing & Communications can be reached at mac-flint@umich.edu.