UM-Flint faculty, students help U-M on the path to carbon neutrality

Equipped with a tape measure and Trimble GPS device, Wildlife Biology majors Nicole Blankertz and Caleb Short have spent their Friday afternoons measuring and cataloging UM-Flint's trees. By identifying the species and DBH (diameter at breast height), it is possible to calculate a tree's ability to capture carbon dioxide and divert it from becoming a greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.

Caleb and Nicole are completing this work as part of a biosequestration internal analysis team, a group comprised of six students from UM-Flint and Ann Arbor and led by UM-Flint Biology faculty members Heather Dawson and Rebecca Tonietto. The team is charged with providing key insights on the biosequestration capabilities of U-M land holdings to the President's Commission on Carbon Neutrality (PCCN).

What is the PCCN?

Close to a year ago, University of Michigan President Mark S. Schlissel announced the formation of the President's Commission on Carbon Neutrality. Consisting of U-M experts and community partners, the PCCN is tasked with developing recommendations for how the U-M system can become neutral in carbon emissions.

While the PCCN is responsible for making the formal recommendations that lead U-M to carbon neutrality, internal analysis teams provide in-depth research and analysis on a specific topic—in this case, biosequestration. The commission's final recommendations are due in December 2020.

PCCN co-chairs Stephen Forrest and Jennifer Haverkamp will talk more about U-M's path to carbon neutrality at UM-Flint on February 25 from 10:30-11:30 a.m. in the KIVA.

Biosequestration?

Human-influenced global climate change is caused in large part by the burning of fossil fuels, which releases greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Biosequestration is essentially the opposite of that process.

"When we burn fossil fuels, we release the large amounts of carbon that those plant fossils have stored—sequestered—in their tissues. Biosequestration relies on the environment—plants, soil, water—to recapture those greenhouse gases from the air and bring them back into the Earth," explains Dawson.

So while other internal analysis teams consider how U-M can eliminate or reduce carbon emissions in the first place, biosequestration works in tandem to capture emissions that cannot currently be eliminated.

More than Michigan Land

The biosequestration team has three main goals:

- Assessment of current U-M landholdings

- Categorization of land use on these properties

- Evaluation of possible land use changes

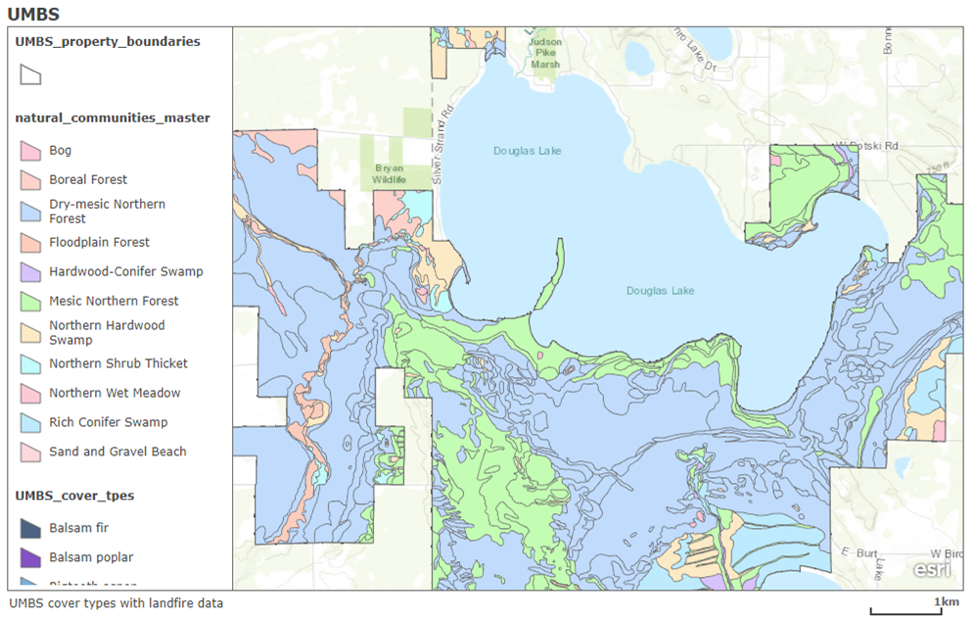

The team has used a combination of Geographic Information Systems techniques and software to classify the different types of University of Michigan-owned land. For example, the University of Michigan Biological Station in Pellston, Michigan, is largely dry-mesic northern forest; classifying land cover types provides insight into the biosequestration capabilities of a particular property.

Classifying all of U-M's land is no small task, as the university owns close to 21,000 acres of property. In addition to the expected holdings around Ann Arbor (3200 acres), Dearborn (175 acres), and Flint (75 acres), there are more far-flung pieces of U-M real estate. Camp Davis, a site dedicated to geology and natural science research, consists of 120 acres just south of Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Identifying Opportunities

After classifying the land, the next task is to identify possible land use changes to increase U-M's biosequestration potential. Perhaps an area covered by regular turf grass could be replaced with natural short-stature grasses that not only sequester more carbon, but also don't require regular mowing, adding to the university's overall sustainability.

While some suggestions could be relatively straightforward to implement, there are often many competing priorities to consider, explains Tonietto.

"Some areas may contain environmental contaminants where you can't disturb the soil … There is a property managed by the School for Environment and Sustainability in Ann Arbor that holds a tree species protected by the Endangered Species Act … And there may be construction projects planned that make a property unsuited for land use changes," said Tonietto.

"We want to come back to the commission with recommendations that can actually be undertaken—projects that both U-M and our community stakeholders can get behind."

Purposeful Work

When Blankertz first came to UM-Flint, she hoped to get involved with research opportunities. Now in her final semester, Blankertz's experiences have far exceeded her initial expectations.

In Summer 2019, Blankertz worked with Dawson on the Flint River Ecology Study, investigating the river's ecology before total removal of the Hamilton Dam on campus. Working for the PCCN as part of the biosequestration team is a perfect continuation of her research experience.

"I never expected to be a part of something like the PCCN, but I think getting involved is very important; to look for ways we can positively impact climate change," Blankertz says. "I am planning on attending grad school, so both the Flint River Ecology Study and this position [on the commission] have given me a lot of field experience as well as more knowledge with Geographic Information Systems."

Tonietto values the chance to use her years of experience as a conservation biologist in such a meaningful project.

"You spend years in your office and the field to publish work that you hope policymakers will read," she said. "With this analysis team, our recommendations are going straight to the people who can make changes. And it's so exciting that some of our students get to be a part of this, too."

Related Posts

No related photos.

Logan McGrady

Logan McGrady is the marketing & digital communication manager for the Office of Marketing and Communication.