The past, present, and future of African Literature Today

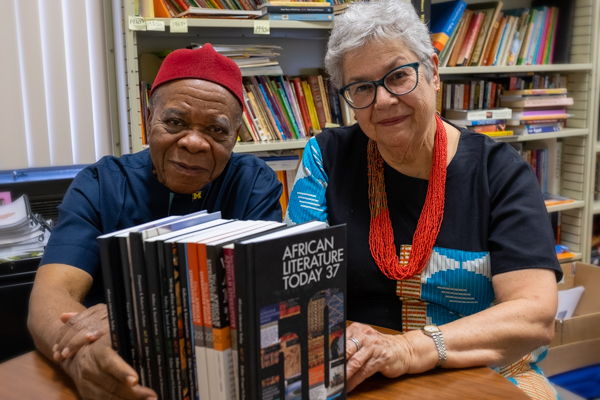

Two UM-Flint faculty members serve in key roles for African Literature Today, which is the oldest international journal of African literature in the world. Africana Studies professor Ernest Emenyonu is editor of the journal, and Dr. Patricia Emenyonu, a lecturer in both Africana Studies and English, is an assistant editor. The Emenyonus, who are married, shared their thoughts about the evolving nature of the journal, their roles, and more in this Q&A with University Communications & Marketing as part of Africa Week 2020.

Can you describe how you became involved with African Literature Today?

Professor Ernest Emenyonu: African Literature Today (ALT) is the oldest and best-known journal of African literature in the world today. Founded in London in 1968, it is published annually simultaneously in England, the United States, and Africa in the third week of November. The founding editor Prof. Eldred Jones – a world-renowned Professor of African Literature from Sierra Leone, West Africa – edited the journal for thirty years. When he retired from the editorship, I was appointed the editor in 2000. In the course of 30 years, Professor Jones had edited 23 issues of the journal. The first issue that I edited was ALT 24. The most recent issue, ALT 37 was published in November 2019, marking the 50th anniversary of ALT. I have edited 14 issues of the journal since 2002 when I joined the University of Michigan-Flint as full professor with tenure and chair of the Department of Africana Studies.

What role do you see the journal serving within African literature and literature overall?

Professor Ernest Emenyonu: ALT is the apex journal in the field of African literature. Since its inception over half a century ago, it has performed a number of roles for literary scholars all over the world. It introduced to world literature in the middle of the 20th century a new type of writing from the African continent, in particular, the African art of the novel. Chinua Achebe's classic novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), marked the beginning of the modern African novel. Achebe opened the door for many other African writers from all parts of the continent. The new African writing in European languages (English and French in particular) grew in leaps and bounds that saw four Africans win the Nobel Prize for Literature in the last two decades of the 20th century. This 'new kid on the block' gave rise to the question among readers and critics, 'What is African literature'? How is it different from literatures already known to the world? Some people simply identified it as an 'appendage to British and French' literatures since much of the writing was in those two languages. It did not take long, however, to prove this view wrong.

The discourse that followed surrounded issues of definition and critical standards of evaluation. This new literature by Africans about Africa, intended to be an essential part of world literature, invariably needed companion literary criticism that addressed issues of standards for assessing its quality and impact at home and abroad. In response, Heinemann Publishers, London, which had the largest list of African authors, took the lead and founded African Literature Today. According to its founding editor, Eldred Jones, "The purpose of the journal was to provide a forum for the examination of African literature…(Over the past 50 years, the journal) has provided "a body of critical opinions against which the literature can be studied" worldwide. The series continues to invite articles on the works of African writers, as well as providing a forum for 'growing' and mentoring budding creative writers and emerging literary critics.

How has the journal changed over time?

Professor Ernest Emenyonu: In the past five decades, the African writing community – like the series – has grown, adapted, and responded to new ideas, environments, and times, manifesting in the process, the capacity and flexibility to meet the challenges that come with time and space. Devoting special issues to topics such as: "New Women's Writing", "Focus on Egypt", "Diaspora (Migration) and Returns in Fiction", "Queer Theory in Film and Fiction", "Environmental Transformations", to mention but a few, is evidence of the series responding to the challenges of the times. So also is the inclusion of two new sections in ALT namely, "Featured Articles", and "Literary Supplement." Both creative writers and literary critics are happy with these innovations. Within themed volumes, unique and exceptional articles outside the theme are published under "Featured Articles." Under Literary Supplement, poems, short stories, and one-act plays are published.

How do you factor in Africa's size and diversity when selecting content for the journal? How is it decided what theme or issue to explore within a specific issue? Can you describe the range of contributors to the publication?

Professor Ernest Emenyonu: ALT serves the interests of readers and literary scholars in Africa and elsewhere in the world. The editorial board consists of experts in African literature appointed based on their expertise in the field (from the UK, US, Africa and the Caribbean). The managing editor is British. The publishing company, James Currey Publishers, is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd., Suffolk, UK/Rochester, New York, USA. The editorial board, headed by me, makes decisions on 'what theme or issue to explore within a specific issue.' Alternating themed with occasional non-themed volumes, a policy put in place by the editorial board a few years ago, has been well-received by literary scholars and will continue.

The best way to answer the question about 'the range of contributors to the publication' is to use as example, ALT 38 that will go to press next month (February). The volume, which is on the theme "Environmental Transformations", has 10 articles as follows: Louise (Stellenbosch University, South Africa), Sule (Ibrahim Babangida University, Nigeria), Jerome (Murdoch University, Australia), Syned (University of Malawi, Southern Africa), Juliana (Ghana), Sandra (London, UK), Eunice (University of Yaoundé, Cameroon), Katherine (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Michelle (School of Oriental & African Studies, London University), James (Hobart and William Smith Colleges, New York).

How would you describe the current state of African literature?

Dr. Patricia Emenyonu: Ironically, the more we try to limit access to others to the United States, the more the world of ideas brings us closer together. The local and the global as the great socialist-feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi has stated has become the "glocal." African literature has seen an explosion of talent gain recognition on the glocal stage. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction with her novel Americanah in 2013. Her TEDx Talk, turned book, We Should All Be Feminists, was incorporated into the Beyonce song "Flawless." In 2007 her novel, Half of a Yellow Sun won the Orange Prize. And in 2008 she was awarded the MacArthur 'Genius' grant. Although she is the 'rock star' of contemporary African women writers, she is not alone.

Let me identify a few more African writers who have received international recognition for their books in the form of established literary prizes. Aminatta Forna (Sierra Leone/UK) received the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in 2007 for her novel Ancestor Stones. In 2009, Uwem Akpan (Nigeria) won the same award for his Say You're One of Them. And the prolific Helen Oyeyemi (Nigeria) won it in 2012 for her novel Mr. Fox. Not exactly a scholarly prize, but certainly being selected by Oprah for her Book Club brings wide publicity and a kind of stardom to any author. Uwem Akpan's Say You're One of Them was selected in 2009. Imbolo Mbue (Cameroon) burst on the scene with her debut novel Behold the Dreamers, also an Oprah Book Club selection in 2017. The young Ghanaian female writer, Yaa Gyasi won the National Book Critics Circle's John Leonard Award for best book in 2016 with Homegoing. We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo was published in 2013 to much critical acclaim. She is the first black African woman (and first from Zimbabwe) to be short-listed for the Man Booker Prize. Here in the US it won the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award. And in Flint, Michigan, it was selected to be our Common Read book.

The list of African writers and their awards could go on and on. These global literary giants are attracting a new generation of readers to African literature. Some of their stories bridge Africa and the United States or Africa and Europe. Just google their names and a wealth of information about their accomplishments comes up. It is an exciting time to be teaching African literature to Americans. No doubt about it. The issues and concerns raised in these works are often universal and relevant to our students at UM-Flint: immigration, identity, equity, and inclusion are part of an on-going discussion on this campus. African literature can help to bring the change-for-the better that we seek.

What would you say has been the most significant accomplishment of African Literature Today? How does your role within the journal contribute to your role within UM-Flint, and vice versa. How does this benefit the educational experience of UM-Flint students?

Dr. Patricia Emenyonu: ALT has provided a consistent outlet for African literary scholars to reach an international audience. Through themed issues, it has encouraged researchers to expand their horizons in areas of scholarship often neglected in the past – Queer Theory in Film and Fiction, Children's Literature and Story-telling, Orature in African languages. Themed volumes brought into focus places and genres – "Focus on Egypt", "Writing Africa in the Short Story", "Film in African Literature", "Diaspora and Returns in Fiction", "Recent Trends in the Novel" are just a few examples. Being on the 'frontier' of modern African literary criticism is a pretty heady place. At the annual African Literature Conference, the editorial board meets and discusses the direction of the journal. What themes will we choose for the future issues of ALT? What panels can be part of the next ALA Conference which will help to gather ideas and discussion around our themes for the next journal? How can we mentor rising scholars in the field of African literature by encouraging them to contribute articles for publication in ALT and to provide important feedback through blind editing of these articles?

The kind of editing that I do for the journal relates to the kind of teaching that I do in the classroom at UM-Flint. How are ideas supported through reference to the work under study? How do writers avoid the tendency to retell the story rather than analyze the story? How can we make our students aware of the exciting world of modern African literature through text and media. I sometimes joke that YouTube is my best friend in the classroom. And my PowerPoint presentations are peppered with pictures taken from the internet to illustrate characters, places, and items that we are reading about in Women Writers of the African World or Introduction to African Literature. We can listen to the authors who are interviewed by NPR or other types of media. These are not dead white men that we are studying. Although a black dead man (Chinua Achebe) is still read and his work forms the foundation of our study of African literature. We expect our students to be part of the glocal scene when they graduate. Why limit their experiences and exposure to what they already know? Let's expand their reach and make them citizens of the world.

Related Posts

No related photos.

UM-Flint News

The Office of Marketing & Communications can be reached at mac-flint@umich.edu.