Flint Neighborhood History Project continues and expands with ACLS funding

Associate Professor of English Vickie Larsen and community partners recently received grant funding to launch phase two of the Flint Neighborhood History Project from the American Council of Learned Societies' (ACLS) Sustaining Public Engagement grant program. This urban memory project documents and interprets residents' stories and artifacts to develop a physical and digital archive, create a museum exhibit, and develop a set of digital visualizations of life in Flint neighborhoods as it is remembered by residents.

Seed funding from the Office of Research MCubed initiative allowed the research team to launch the project in 2019 and to partner with community organizations such as the Community Foundation of Greater Flint and Flint's Neighborhood Engagement Hub to secure Jordan Brand foundation funds. The project's widespread interest in the community and interruption from the pandemic led the team to seek additional funding, which it found with an ACLS Sustaining Public Engagement grant program designed to bolster publicly-engaged humanities projects affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The funds for this grant program emerged from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP) initiative. The Flint Neighborhood History Project received $137,000 to support the project into 2023.

The project team is currently engaged in a "city-wide year of listening," recording oral histories of Flint residents' lived experience of American history at the neighborhood level. Phase two will continue that work and add the creation of community-based archives, a digital repository, and exhibits. Larsen plans to utilize two software platforms to exhibit images, documents, audio, and video files: digital exhibit software that communicates with structured metadata to locate relationships between files and geospatial software that connects narratives and images to physical spaces using geographic information systems (GIS) mapping tools.

"Many of our storytellers are displaced residents of neighborhoods that were razed fifty years ago for freeway projects–the Southside and St. John," says Larsen, "but every Flint neighborhood has its own stories and, in practice, our narrators come from all over the city."

According to Tom Wyatt, executive director of the Neighborhood Engagement Hub, "these neighborhoods are more than what happened to them; they're what happened in them. These days, where everyone fancies themselves a scientist, we all have our hypotheses about why things changed from x to y. Combining research with this oral history project is helping to erode false assumptions."

Project beginnings

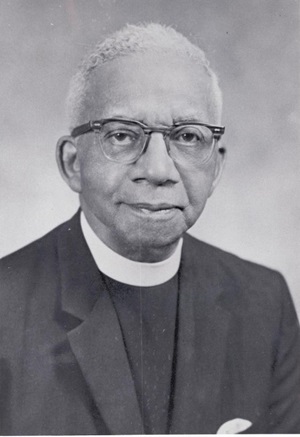

Larsen became interested in the project when asked by a local church to research their founder, Norman Dukette, one of the first black Catholic priests in America. She connected with former Southside residents and found that Dukette's history was part of a neighborhood's history. Dukette had worked from 1929 to 1980 in the Southside, a neighborhood that was segregated by federal redlining practices in the 1930s and destroyed by urban renewal initiatives in 1970.

This work is more than a research agenda for Larsen. "Things I was reading about academically became things I'd been hearing about in my own community for several years, and I became interested in the nexus of document-based history, communal memory, and personal narrative."

The Community Foundation of Greater Flint (CFGF) brought together Larsen, the Neighborhood Engagement Hub, and the Sloan Museum of Discovery to see if this work might become a multi-partner collaboration. "Serendipity" is how CFGF Outreach Director Lynn Williams describes the collaboration. The CFGF was already engaged in work to help mitigate the impact of systemic racism through the Truth and Racial Healing and Transformation initiative. That work included racial healing circles led by trained facilitators to acknowledge the common threads of humanity and jettison notions of a hierarchy of human value. Williams describes the related goals of the FNHP as, "unearthing stories, narratives that have never been told by people in these communities and lifting it in order to change the false narratives that currently exist." The team developed the shape of the project, wrote the grant, and the Jordan Foundation selected it as one of 18 projects funded by their community grants program.

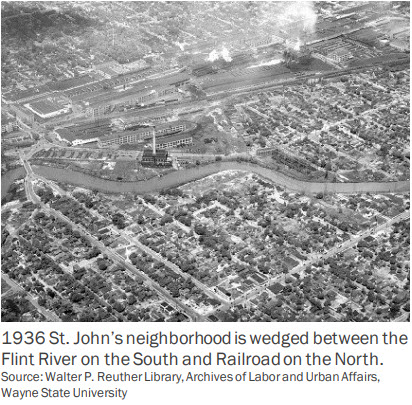

St. John Street

For James Wardlow, the president of the St. John St. Historical Committee, the history of the St. John neighborhood has been a long-term initiative. Once the neighborhood was destroyed and the residents displaced, the committee's work came to include maintaining relationships between former neighbors. Wardlow feels a strong connection to the last building standing in the St. John neighborhood: a vibrant community center built in the 1950's, then Flint's police academy, and now a marijuana dispensary. The sale of this public building for commercial use validated Mr. Wardlow's position that the history of his neighborhood was not being fully understood.

The picture painted of the St. John Street neighborhood by Wardlow is of a beautiful community. "This was a place with camaraderie," he said, "The St. John Street neighborhood was a place where everyone looked out for one another; parents across the neighborhood watched one another's kids." Wardlow remembers playing in friends' yards, most having big vegetable gardens. "We had gardens, fruit trees, and grape vines growing everywhere."

St. John and Southside were the two neighborhoods in the city where housing covenants did not exclude African American residents in the mid-20th century. Housing covenants prevented African Americans from purchasing home in other areas of the city until as late as the fall of 1967 when the city narrowly passed an open-housing ordinance (one of the first of its kind in the country, and the city's first Black mayor, Melvin McCree, had to threaten to resign for the City Commission to pass it). Both St. John and the Southside were racially mixed. "You had your Polish community, you had the black community, you had the Germans. You had everybody there and everybody talked to each other and everybody communicated with each other and everybody knew each other on a first-name basis," said Woody Etherly in Bronze Pillars, a book written by Rhonda Sanders based upon an earlier set of oral histories.

Of course, not everyone remembers St John as idyllic. In an East Village Magazine story from 2016, St. John Street neighborhood remembered by McCree Theater's Winfrey, Robert Thomas details a Tendaji Talks seminar in which Charles Winfrey recalled crowding in the neighborhood, "Sometimes you'd have four or five families living in the same residence. That's just the way it was because of the restrictions in other areas." Winfrey also referred to activities along St. John street. In his account from Bronze Pillars, former resident James Wesley warns against romanticizing St. John, saying, "Throw it out of your mind that it was a nice place to be… There was too much fighting over there and off-the-wall businesses. No such thing as shopping over there. Nothing but joints."

Some of Winfrey's critique was based on the environmental quality of St. John. "Soot would rain down upon the residents." He wasn't alone in that observation. Olive Beasley, director of the Flint district of the State Department of Civil Rights pointed out the effects of soot clouds, saying that "people were suffering from all sorts of respiratory diseases….Cars would get speckled, and the paint peeled off from the fallout. Houses peeled too."

When the families and businesses of St. John were displaced, "the biggest loss was the sense of community, including the network of businesses in the neighborhood," Wardlow explains. "The perception is that it was a ghetto. It was not. The homes were nice; lawns were manicured; people took great care and pride in their homes. It was not until it became known that the urban renewal projects were going to be taking away the homes, razing them to the ground, that folks stopped taking care of them." St. John was a complex neighborhood in the memories of its residents.

Carriage Town

Larsen visited Randy Carter and his mother Margie Carter, who both grew up in Carriage Town and described the neighborhood throughout the 20th century. Margie Carter was born at home on Patrick Street in 1916 and raised her family on Stone Street. Both grew up viewing the presence of Indigenous human remains as a distinctive feature of their neighborhood. "There's bones from Water Street to the other side of 5th Avenue," Maggie Carter declares. Her memories include milk and ice deliveries, helping her father with his well-digging business as a child, and visiting the glamorous businesses on Saginaw Street in the 1920s:

"I remember on Friday, my mom would say, 'If you kids get the house good and clean, and all your chores done, we'll take the streetcar downtown tomorrow.' The streetcar went down Third Avenue, and you could take one most anywhere in the city."

Margie Carter

Randy Carter described the experience of automation inside the General Motors plant where he worked and the ground beneath the factories being saturated with oil and chemicals. The Carters, like all of the FNHP narrators, experienced the history of their city and their country from the vantage point of life in their own neighborhood and workplaces.

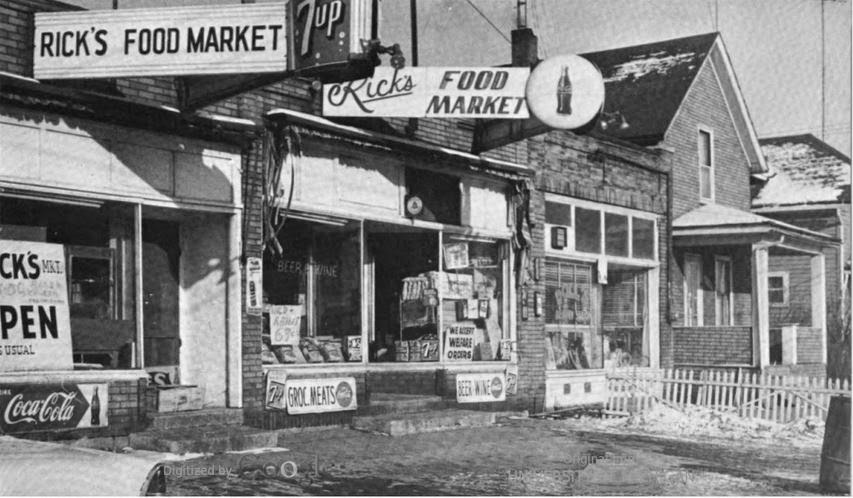

The importance of businesses to a sense of community

Larsen reports being surprised by how central businesses are to the memories people have maintained of their neighborhoods. 105-year-old Margie Carter becomes animated when describing the downtown candy stores. She, like many narrators, also emphasized the relationships between residents and neighborhood grocers. Wardlow describes the business district of St. John, saying. "We had grocery stores, funeral homes, nightclubs, dry cleaners, and hardware stores. We didn't have to go outside the community for anything except maybe a large appliance." The neighborhood had its own coal company, ice house, jail, and slaughterhouse. "When we had to relocate," Wardlow continues, "all of those resources were lost to us, and at the same time resources like the Hamady Brothers grocery store all moved out of town at that time as well, following that white flight into the suburbs."

The Floral Park neighborhood in the Southside, where Flint's first black homeowners settled in the late 1800's featured Walker's department store, Reed's Drugstore, Raymond's barber shop, the Sportsman's Club, and the Golden Leaf. According to Wyatt, "They had that life, and these things were taken away from them. It's really helpful to show the context, break open the oversimplifications, and present thoughts about how one would react to that situation in their own neighborhoods."

The research team

This project includes a large team of people from various organizations each contributing their talents in large and small ways, including faculty and staff at UM-Flint, the Sloan Museum of Discovery, the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, the Sylvester Broome Empowerment Village, the Michigan Libraries Digital Scholarship Service team, the Neighborhood Engagement Hub, neighborhood organizations, and churches. If you would like to be involved in this project please contact Vickie Larsen at vlarsen@umich.edu.

Learn More:

"St. John Street Remembered" by Michael Evanoff;

"Bronze Pillars: an Oral History of African-Americans in Flint" by Rhonda Sanders;

"Memoirs of St. John Street" by Craig Hall;

"Demolition Means Progress" by Andrew Highsmith;

"Teardown: Memoir of a Vanishing City" by Gordon Young.

Related Posts

No related photos.

Rob McCullough

Rob McCullough is the Broader Impacts Manager for the College of Innovation & Technology. He can be reached at romccull@umich.edu.